One of my concerns related to our team is that we do not have a member who has UI professional experience. However, all this was an excellent chance to test some ideas.

Game interface

Just to make it clear: UX and UI are not the same thing. The User Interface (UI) is related with anything that is designed to be an information device, in which user can interact with. This can include the display screen, keyboard, mouse, and desktop display. This is also how users interact with apps or websites. User experience (UX) is the art of a product design planning so the interaction with completed products will be as great as possible. This includes the interaction with end-user on a several IT systems. Where UX Design is a more analytical and technical field, UI Design is closer to what is called graphic design, although the responsibility is rather complicated. (Kristiadi 2017).

What is the purpose of the UI in the first place? Usually, the UI represents a (potentially frustrating) barrier between the player and the game. The player wants to take an action in the game and must translate that desire into a physical action, such as a series of button presses. The goal of the UI designer is to create a set of controls that is as transparent and easy to use as possible, so that the player can concentrate on actually playing the game rather than mastering the controls. (Brathwithe 2009)

As I read a few weeks ago on the pages of The Art of Game Design – A book of lenses, a good practise to create an interface, especially not being my area of expertise, is the ‘top-down’ approach that basically consist on copy another interface from a well know game genre. ‘This can save you a lot of design time and has the benefit of being a familiar interface to your users’ (Schell 2015). It can feel like cheating, but you’re only going to be as good as the stuff you surround yourself with they say. In our case it was more of an unconscious stealing from the classic 8 bits games of our childhood. It was really satisfying to add this touch to the demo and I think that it reflect very well the spirit of the team and our like.

Even if we did not follow the same systematic approach to figure out the new interface, I’d like to synthesise a few of the 9 tips that the Schell explains at the end of chapter fifteen of his book. We surely use them in some way or another:

- Steal (with a few tweaks a cloned interfaced can morph into something quite different)

- Customize (the opposite of the previous one, you design your interface from scratch, by listing information, channels and dimensions).

- Design around your physical interface (the same game, very different interfaces: touch interfaces, motion interfaces, mouse and keyboard, gamepads, etc. Trying to design a game independent of any particular interface is usually a path to a dull game).

- Theme your interface (find a way to tie the interface all together with the rest of the game experience).

- Test, test, test! (no one gets an interface right the first time!).

C’mon baby light my fire!

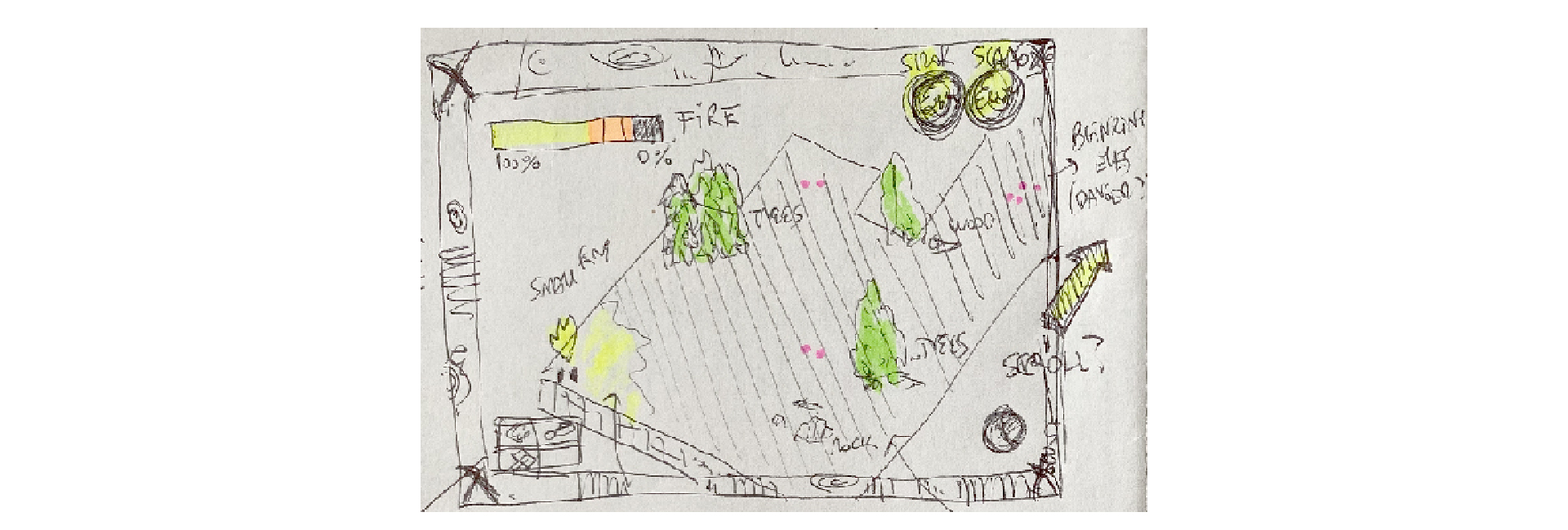

At the beginning, we had a health or energy counter and a fire counter (see figure below). This fire, as I explained several times before, also represents the time we had left to live. Having so many counters for the same thing did not seem right, although we still tried with two of them on the screen.

We even discussed the possibility of using something like a tattoo on the character’s back as an indicator; because it seemed quite poetic to think that, the fire also symbolized the inner strength, the will to survive of our primitive heroes.

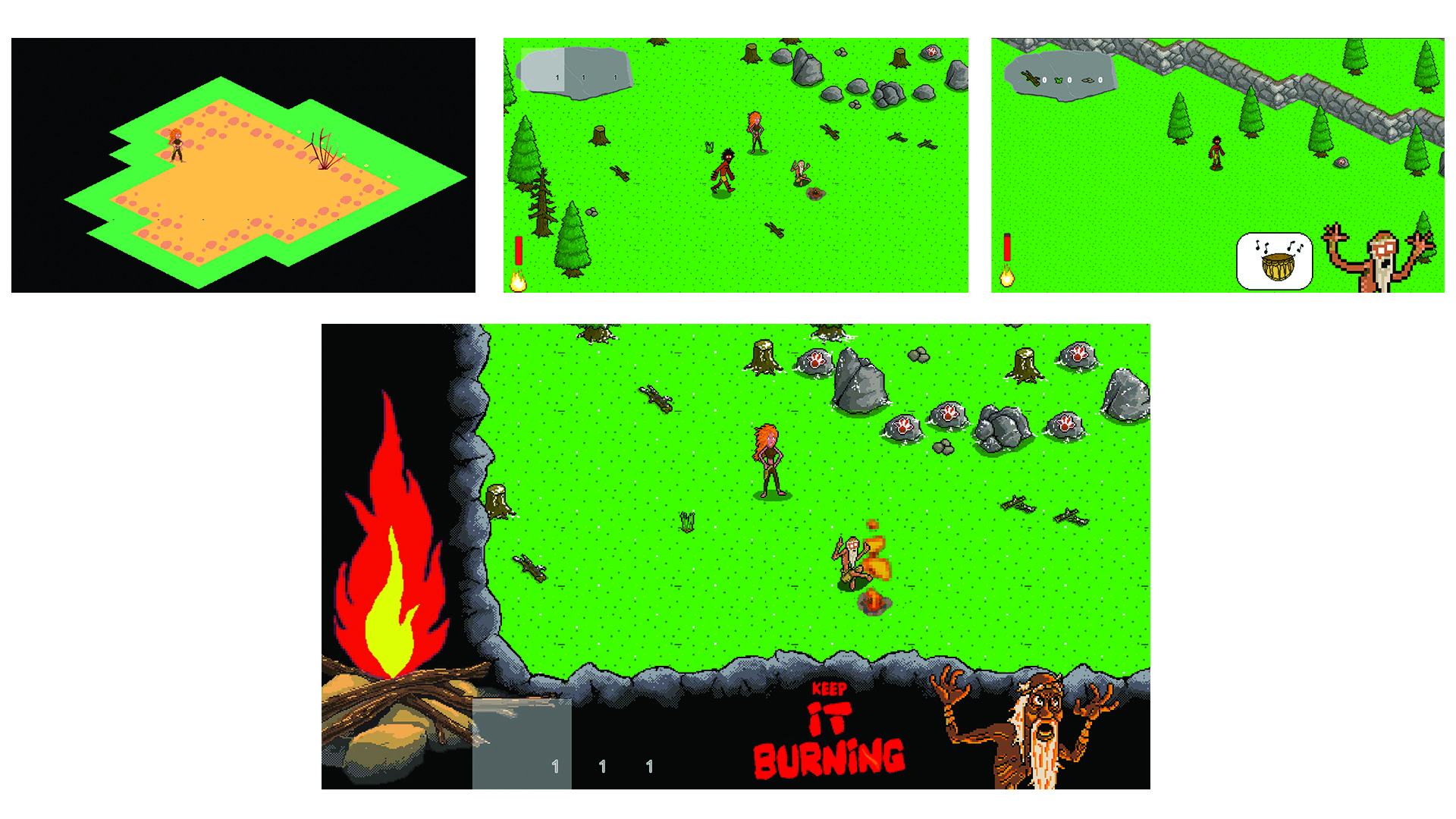

As simplifying is always a good option, I suggested then the idea of joining all the gauges into one. A big flame that would grow or weaken on one side of the screen depending on what the player was doing, discarding for the moment the random location of elements or even the use of procedural algorithms to generate the levels computationally.

I am pretty satisfied with the way in which the prototype looks. The art of Will looks excellent, and we should have the primary mechanism already set. It is also a significant achievement to go on within the deadline established.

Player groups towards more playtesting

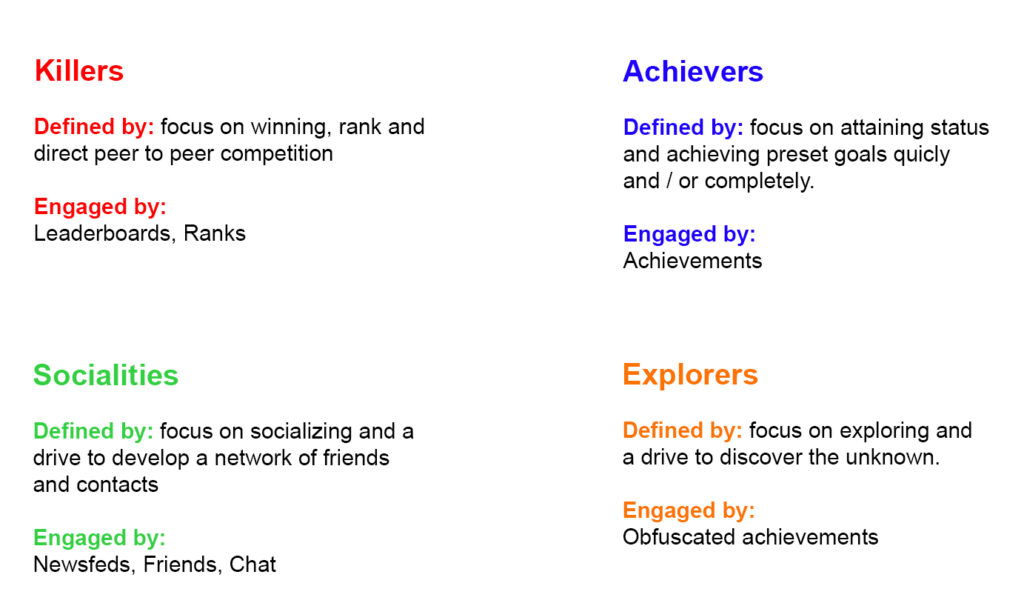

As the playtesting session is scheduled for next week I start reflecting about player groups and audiences. Once again, my current favourite magazine on video game development, Wireframe, offered my an interesting lecture on this subject. Appeared on Issue 39 from June 2020, the article centers on how most indie devs often design games that they wanted to play (and our team is not the exception!) when it would be better to create games on what players wanted, rather an individual’s or studio preferences. Richard Bartle created a test to group players based on their affinities. This model divides players into four types:

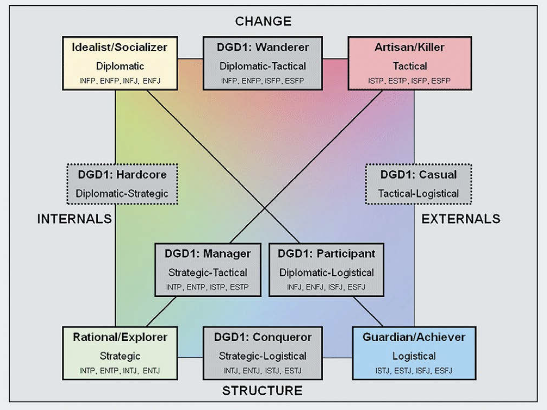

We believe that our players will fall into the Explorers and Achievers categories, which is somehow unsettling as it represents only half of our potential market. Fortunately things are not so simple as we can see in another study, where Bartle’s theory has been expanded with more detailed psychological breakdowns of player behaviour.

Rather than assuming everyone else likes the same things you do, there was a way to design a game targeted at one or more groups.

All these decisions, whether made consciously or ‘accidentally’ by your personal preferences, send a message saying either, ‘This game is for you,’ or ‘This isn’t a game you’re going to enjoy’. (Maine 2020)

The article also explains why all this must be taken into account: if some parts of the game are more to the liking of a certain type of player -for example, adventurers- but if at the same time and for no reason at all, other parts delight those who identify themselves within the group of killers, we have a problem since the content will end up confusing everyone and the experience will not be completely satisfactory for anyone.

Another interesting point to keep in mind is that once we have identified the ideal player for our product, we need to make sure that all marketing efforts communicate this clearly.

Finally, knowing the type of audience also makes it easier to reach them, by focusing on the online communities that bring them together.

Weekly Challenge: marketing personae for Keep It Burning

Name: Olivier Atomu.

Role: Elementary school student.

Demographic: 8 years old.

Description: He’s a very active kid. Loves to play chess, go to acting classes and watch YouTube videos on his iPad while collecting Pokemon trading cards. He is the youngest of three siblings. He is the heir to all his older brothers’ toys, video games, magazines, and books. He spends at least 2 hours/day playing free games from the App Store or independent platforms like Roblox. He primarily plays adventure and collective card games. He has no access to a credit card or permission to install apps on his devices, so their parents are well aware of most of his online activities.

Challenges: lot of free time but no monetary resources.

Key quote: Can I install this game dad? It’s free!

Intellectual Property: my experience

Last week’s reading is related to the legal aspects of intellectual property as it relates to video games, based primarily on UK laws and regulations. Regardless of nationalities, this is a topic that cannot be ignored by any independent artist, let alone indie developers.

In a nutshell, intellectual property is an idea or a collection of ideas that is owned by someone or something and is the result of creative work. A quick scan of the shelves of any game retailer or online site reveals just how pervasive IPs are in games. In fact, in any given year, the majority of best-selling game titles are derived from pre-existing IP. These games are either sequels to previous games in the series or licensed titles usually coinciding with a major movie release. (Brathwhite 2009 : 121-122)

Types of IP

Original IP: developed by or for the IP holder and, in the case of the game industry, is owned by the publisher or developer. The IP has yet to be attached to any other game or any product in any medium.

Licensed IP: is a pre-existing IP that is licensed for use in a video game by the publisher or developer. Publishers pay a fee or a royalty to use IPs in their games.

Sequels are subsequent releases of either original or licensed IP: subsequent releases of either original or licensed IP. Can be expansion packs, mods, actual sequels, yearly releases or even spiritual successors from it.

Copyrights can provide powerful protection for your original work, such as a literary, dramatic, musical, or artistic work, but there are limitations.ou cannot copyright an idea, only the expression of the idea. For instance, you could copyright a design document for an auto racing game, but not the idea of an auto racing game. ( Perry 2009 :64)

In my case, after the Kickstarter campaign and obtaining a production grant that culminated in the publication of my adventure game, I don’t think I’ve gone too far off the path that the vast majority of indie developers go through, read with reduced budget. It is very common that within the money destined to create a game, the legal or administrative costs derived from the paperwork related to copyrights are not considered. Much less, thinking about including in the team an external lawyer or even take the minimum legal precautions. In fact, it is widespread behavior to wait until a few weeks before the game’s launch to decide to take any kind of legal advice.

In addition, in countries like Swizerland, a minimum consultancy can cost the same as several weeks of production. It is difficult to find an expert in IPs who also understands the video game market, so a rendez-vous with a lawyer who is not very knowledgeable about these issues usually generates more doubts than certainties. It has happened to me that after consulting a couple of legal advisors I ended up asking for answers to other fellow developers, who gave me all kinds of advice, many of which could be described as ‘legal urban legends’. Hard to believe in the city where OMPI / WIPO itself has its international headquarters.

The first thing you learn is that ideas cannot be protected, and therefore, the most logical step is to patent a name or trademark. A puzzling beginning if there is one. It is also very common for a small development studio to need to hire freelance artists, musicians or programmers so again we have the issue of contracts involved.

Being the video game industry an incipient and almost ignored market in this country, the best thing to do is to try to go through the family tree to find a law school graduate who can lend a hand. Otherwise, welcome to a black hole where few creators dare to stick their heads!

I personally know that it is vox populi among amateur developers to send themselves a sealed envelope containing a brief description of their own game, some characters and why not a hexadecimal dump of the game code. Sounds weird, yes, but after a bit of research such a procedure has some legal basis, even if for practical purposes it is very inappropriate.

Other advice I have received has been to have a domain name identical to the game title, and to publish a short demo version on as many platforms as possible. In theory, this would set some sort of precedent as to the origin and creation of the program in case some third party claims authorship. It is clear that this is a preventive measure in case we are judicially attacked, although defending our rights before a local court -or in the worst-case international- would be extremely complex and costly and most Indies can’t afford that. Another of the big problems related to video games: by publishing on platforms that are generally foreign (mostly North American), the feeling of uncertainty and lack of protection is not unfounded.

A franchise is born!

There is usually a big idea behind intellectual properties upon which franchises are born, as Dille and Platten explained on his book ‘The Ultimate Guide To Video Games’.

Theme: what is the reason you are telling this story?

Character: franchise characters are well defined. People can understand, relate to, and root for protagonists like that.

Tone: what is it? Light, dark, real, fantasy, straight, comedy. It should be easily defined.

World: a distinct sense of place that anchors the story in the meta-reality beyond our characters.

Missing opportunities due to lack of legal knowledge

Moreover, this is just the tip of the iceberg. In my case, I have had to reject several publishing contracts just because I didn’t have the possibility of paying someone to review them for me before deciding to sign.

While I know that the vast majority of publishers are extremely serious partners of the development teams, almost all of these contracts are written in legal english and overloaded with technicalities specific to our industry, that normal lawyers who are not familiar with the English language or computer jargon, find it impossible to understand. It is as simple as that.

Proof of good faith has been the online publication of the contracts that the renowned distributor Raw Fury made last year.

In 2019, I benefited from the advice and coaching of several experts from the firm Spielefabrique (with German-French offices) who helped me in this matter at the European level, who strongly recommended me to reserve a part of the money destined to the production to register – at least – the name of my product.

The legal advisors of the Pro Helvetia Foundation provided other protection measures to me and although there is no specific consultancy to turn to, I am confident that they are working on this issue to provide indie developers with some kind of advice at affordable prices. For this and other issues concerning this industry on Switzerland we are fighting, trying to get our representatives in the government to listen to our problems and bring us solutions.

Personal and professional goals

If you feel this is a valid case and we should finally start discussing, sustainable funding structures for commercial games: Head over here and sign up: https://www.operationlevelup.

We want to be able to reach everyone who is working in games and interactive media here in Switzerland and in Europe.

Please help to spread the announcement! The topic can use every bit of traction it can get when the media will hear about it today.

List of figures

Fig 1. A sketch I made to start conceptualizing the UI. Image by the author.

Fig 2. Evolution of the UI for Keep it Burning demo (from no interface at all to the final version). Pixel art by Will Ward.

Fig 3. The original fire counter vs the new one. Screen captures by the author.

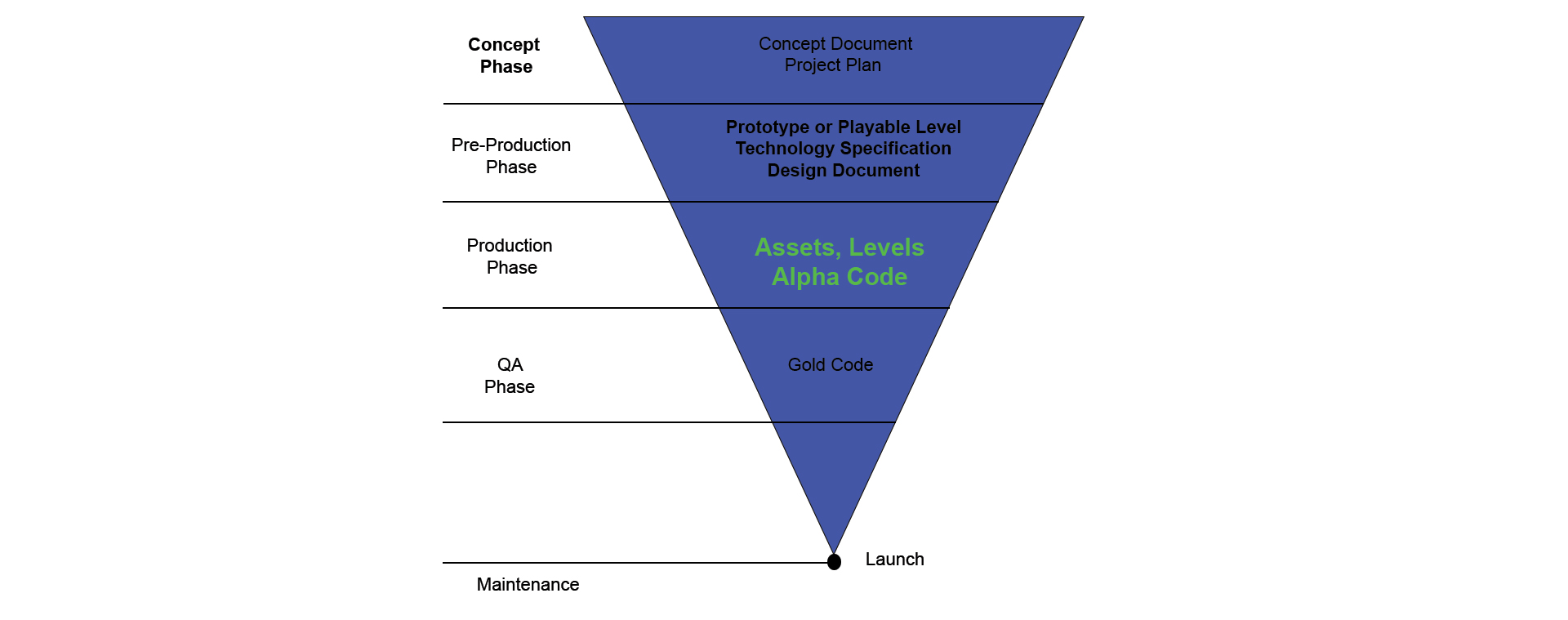

Fig 4. Stage of development for Keep it Burning on Week 8.

Fig 5. Bartle classification of players by Richard Battle.

Fig 6. Unified model, Keirsey-Bartle diagram with Bateman DGD1 Model overlaid.

Fig 7. Level Up initiative call to action.Philomena Schwab / Stray Fawn Studios / Swiss Game Developers Association.

Fig 8. Design protection form for my game Sol 705 mark under Swiss territory.

References

Kleaon, A. 2012. ‘Steal like an artist 10 Things Nobody Told You About Being Creative‘. Workman Publishing Company.

Main, S. 2020. ‘Player groups: how the can help you make the right decisions‘. ‘Wireframe magazine issue 39. Raspberry Pi Publishing.

PC Gamer online 2020. ‘Which game has the best inventory system‘. [online] Available at <https://www.pcgamer.com/which-game-has-the-best-inventory-system/> [Accessed 24 July 2021].

Kristiadi, D. 2017. ‘The effect of UI, UX and GX on video games‘ 2017 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Computational Intelligence (CyberneticsCom) 158-163

Harms C, Jackel L, Montag C. 2017. ‘Reliability and completion speed in online questionnaires under consideration of personality’. Department of Psychology, University Bonn, Bonn, Germany.

Brathwaite B, Schreiber I. 2009. ‘Challenges for Game Designers‘. Charles River Media.

Schell, J. 2015. ‘The Art of Game Design A Book of Lenses‘. Second Edition. CRC Press. Taylor & Francis Group.

Perry D, DeMaria R. 2009. ‘David Perry on Game Design: A Brainstorming Toolbox‘. Charles River Media. Course Technology, a part of Cengage Learning.