Although the topics I have to deal with this time correspond to the readings of a couple of weeks ago (crunching hours, freelance working and collaborations), as they are closely linked I have decided to put them together in this post.

Although the topics I have to deal with this time correspond to the readings of a couple of weeks ago (crunching hours, freelance working and collaborations), as they are closely linked I have decided to put them together in this post.

About crunching hours

Anyone who is minimally involved or follows closely the video game development industry has heard terrible stories regarding crunching stages, especially during recent times where these truths have become known on several occasions, being the most notorious the closure of Telltale Games in 2018, exposed by Kotaku, one of the most respected specialised video game websites at least until a few months ago when its own miseries were revealed. Emily Grace Buck, a lead designer on several Telltale games spoke publicly about how long hours were customary at the company. ‘It’s true we usually worked 50 plus hour weeks. Sometimes 70-80. Weekends were often expected. We were constantly understaffed. Deadlines were ludicrously tight. Our schedules were so close we went from one crunch directly into another’.

Some former employees reported working 14 to 18 hour days or coming in every day of the week for weeks on end. But where most developers go into ‘crunch mode’ in the final months of a game leading up to its launch, they described it as constant, reported The Verge.

For most game developers, the crunch is a fact of life. Of approximately 1,000 developers found that 52% of of those surveyed put in between 40-60-hour workweeks during a crunch period, while 32% put in 61-80 hours or more. Furthermore, the study found it almost always negatively affects the personal lives of developers. (Rivera 2014)

One might imagine that this is a thing of the past, but nevertheless It’s an inevitable evil in a field where most projects have an immeasurable number of unknowns and a marketing commitment to a seemingly arbitrary ship date, continues Rivera in his article. Electronic Arts, Rockstar Games and more recently cases like the Cyberpunk 2077 from polish studio CD Project Red have reportedly been required to work long hours, including six-day weeks, for more than a year, informed Polygon.

Having tangentially passed through not only this industry but also the animation industry it is evident that the latter has been able to handle the situation much better than the former. Although partly related during the last decades, AAA game creation challenges complexities that animated productions do not have to include in their agenda. Junction Point Studios founder and game designer Warren Spector said crunch was the result of working with a host of unknown factors in creative mediums. Since game development is always full of unknowns, crunch will always exist in studios that strive for quality.

However, what about small independent developers?

Feeling part of this group I have to assure that most of the indie creators who have finished at least one game have had to go through terrible tests of courage, will and mental and physical stress. In my case, the last 4 months of development of my adventure game was a real marathon that I had to go through working on the game for more than 16 hours a day -practically from 6 am to 12 pm- including weekends.

During this period I could only focus on deliver the game as well as possible, finishing it, without having space for family, friends or any other kind of recreation. Since at that time my only job responsibility was to publish this product, I could afford such a sacrifice; at least in theory, as I had some savings from a production grant and the proceeds from the Kickstarter campaign, not to mention, of course, the financial and spiritual support provided by my wife and children.

To summarize this situation in one word I can only use the term madness. And that we are talking about a small game of just a few hours of duration.

The terribly sad thing about all this is that what happened to me usually happens to almost every small development team behind games promoted through crowdfunding campaigns or personally funded. I remember that a few months before being trapped in this same problem, I could hardly believe the story of the graphic designer of the adventure game Gibbous, a Cthulhu Adventure who in full nervous breakdown and crying inconsolably talked (min 45:52) about how hard it was to work in those conditions and the impossibility of moving forward. Many are the testimonies that can be found in this regard, some of them crowned with a horde of heavy criticism from the public or journalists, totally oblivious to the sacrifice of the creators.

It is true that, in most cases, these criticisms are accurate -although perhaps not entirely justified- nevertheless if to the complexity of finishing a product of this type is added the pressure of obtaining the subsequent approval of the press and the fandom, the stress levels that the development team has to endure can be devastating. Not to mention the success or failure of sales.

Having learned a little from my experience, when structuring the development of our project I took these factors into account, especially time planning and task distribution. However, on this occasion I had to face certain factors that were unknown to me and somewhat unpredictable, such as the premature departure of a key member of the team. Knowing in advance the possible pitfalls we would be venturing into also helped us not to face overloaded schedules beyond what was foreseeable, and we knew how to balance expectations against realities.

As leader of the group, I believe I took full advantage of this knowledge gained through my past experiences to avoid subjecting the team, and myself, to the dangers mentioned above. I am proud to have finished everything required within the time limits established (even a day before the deadline!) with the satisfaction that each member gave it their best towards the same goal.

Music and sound on Keep It Burning

Although often denied, the musical and sound aspect is as important to our understanding as the visual one. It is true that, not having a music composer in the group, we agreed to use a melody composed by someone outside the team either by order or by acquiring the corresponding track from its author in the case of not finding any audio that suited our needs.

In a recent article from Wireframe Magazine, published on Issue 41, game developer Jeff Spoonhower wrote about this: ‘Many developers struggle with the decision to use free music, ‘buyout’ music, or to hire a professional composer or musician to score their game. Avoid free music if at all possible: it is noticeably low-quality in style and technique, often contains degradation due to compression artifacting, and chances are, has already been used in other people’s media projects. The quality of for-purchase, royalty-free (‘buyout’) music has improved significantly in recent years and represents a step up in quality over free music.’

What emotional tone do we want to establish? What narrative information do we want to reveal to the player through music?

After considering what kind of melodies we were looking for to use in the prototype, it occurred to us that it should be something that reflected the tribal and visceral aspect, such as drums or sounds coming from primitive instruments that we all associate with the times of the caves. But not only for the picturesque but also because it seemed a good idea to unify the concept of fire with the heartbeat -represented by the percussion- with the survival of the members of the tribe. In concordance with the retro style from the graphic we were also looking for a chiptune track as much as possible. Debbie, as the person in charge of providing us with this material, started working on it. Having a large library of sound effects, I made a pre-selection that I sent to Debbs for her to choose the ones she considered most appropriate to put in the prototype.

Bandcamp and SoundCloud are excellent resources for finding established or up-and- coming game composers and musicians. Sites such as premiumbeat.com offer massive libraries of high-quality tracks covering a wide variety of genres. (Spoonhower 2021).

For my part, having worked with freelance musicians and composers for two previous projects of mine, it was clear to me that due to time and budget issues the most convenient thing to do would be to use an online library. One of the disadvantages of not having an in house composer is that searching for a melody or a sound effect among the hundreds available on the internet, either free or paid, can mean long hours of heavy listening.

One tends to think that looking for a nice tune or a convenient sound effect it’s the same as going through dozens of graphic artists’ sites searching for that needed art asset for the game, but personally my ears get tired quickly and I find it exhausting to have to listen to dozens of sound samples one after the other, something that doesn’t happen to me on a visual level. It may seem exaggerated, but it happened to me that after a couple of hours of listening sound effects of all kinds and quality my ability to continue working in other areas of my game development was seriously affected, not to mention headaches.

The act of listening to musical sound is usually considered as a kind of recreation, or an impulse to take a rest. But the music can also be considered as a noise not only from the musical structure and composer’s point of view. In some cases, listening to the music may not be only a kind of recreation from particular professionals it is their work. The people working on this professions are subjected to hearing problem, in the same manner as the noise-exposed workers in an industry. (Hatzopoulos 2017 :168)

Another issue that bothered me is not to fall into the cliché of associating primitive humans with animal skin and bone instruments, so I spent some time reading about this subject in the same way I did when I researched the origins of fire and its use during the dawn of humanity.

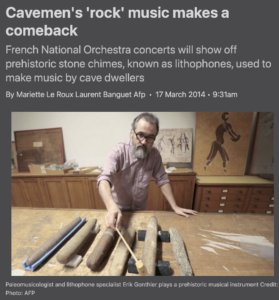

I found some amazing insights from an articled published on about the lithopones, stone rods carefully crafted primitive instruments dated between 2500 and 8000 BC, used by four percussionists from the French National Orchestra during a unique series of concerts in Paris on 2014. After three shows the precious stones were packed again forever. ‘That will be their last concert together. We will never repeat it, for ethical reasons – to avoid damaging our cultural heritage. We don’t want to add to the wear of these instruments.’, music archaeologist Erik Gonthier of the Natural History Museum in Paris, told to the press. Gonthier said he had a long battle to convince other experts the stones could be safely used, with great care, for the upcoming concert, and I can imagine why!.

It was at that time that I remembered that I saved on my hard disk a couple of short compositions that I had not used in my previous game. I vaguely recall that it was a music track (composed by Eric Matyas especially for the demo version of Sol 705) that closely resembled what we needed, so I sent it to the others to get their thoughts. Debbie particularly hoped to find something more appropriate, but this was more than enough to use as ‘dummy’ soundtrack until we found the final musical piece.

As the days went by, Phil proposed to use the music to guide the protagonist’s journey towards his goal. The idea was that the sound of the drums came from the Elder of the tribe, who was calling the others from a farther point up on the map, the objective being that the hero would find his way to the old chaman. This prompted Will to give us a magnificent animated sequence of the little old man playing some rudimentary drums and the whole cemented the first phase of this adventure. Thus, through the old man’s will, a succession of mini-quests would be unleashed that would nourish the game loop of which I have already spoken above.

We also realised that Matyas composition provided some fun as opposed to other musical passages that were too solemn or epic and clashed with the rest of the ‘humorous’ elements of the game, so we kept it.

Using sound effects to bring humour

As I explained earlier, the use of sound, or rather sound effects, is an invaluable tool when it comes to communicating with the player and telling the story. In fact, I am convinced that in some cases a sound is worth a thousand images. Examples of this: the guttural manifestations with which the icon of the old man is presented when he comes out at the bottom of the screen. Drawing the face and part of the torso took several hours of work (and we didn’t even pretend to animate it). Giving him a sound that would catch the player’s attention took a matter of minutes.

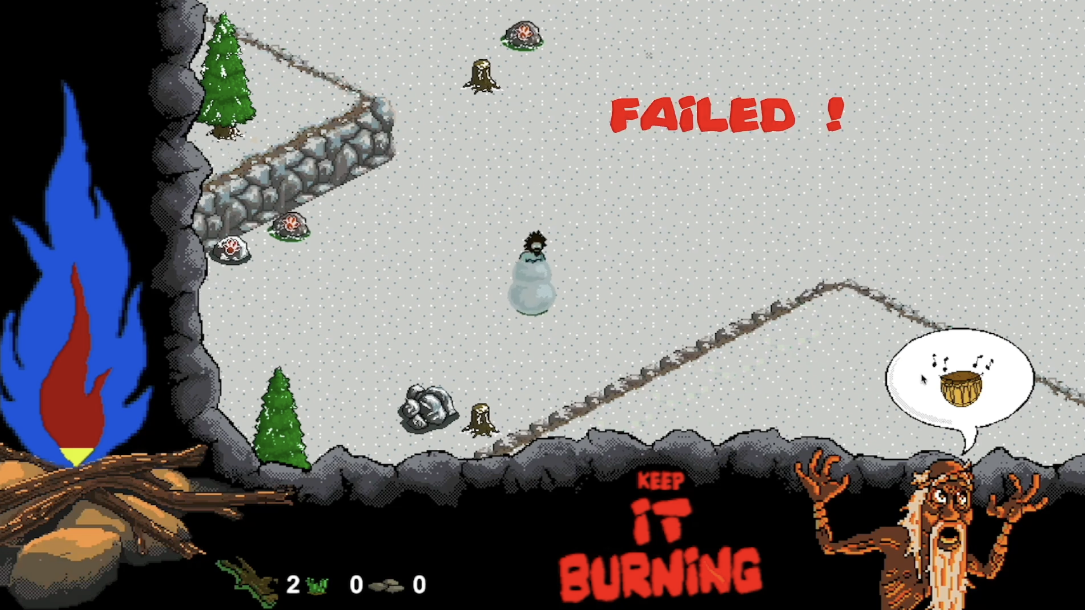

The sound effect of the ice freezing the protagonist’s body with the icy wind in the background conveys a convincing, and even distressing feeling, so I decided to add an element of decompression by including, after this sequence, a funny sneeze. Another simple idea implemented after only a few minutes of work; I didn’t even need to use an animation or any graphic element to go with it since the screen is completely dark during the sneeze… and yet something so simple managed to get more than one laugh during the subsequent sneezes, completely achieving the goal.

We must remember that the humorous component should not be overshadowed by the supposed ‘death’ of the protagonist and his companions.

What we leave behind

As I wrote before, it was not one of my objectives to be the leader of the group. After having lived the stress of creating an adventure game a few months ago, and having produced an animated short film almost at the same time, the last thing I wanted was to put myself in the shoes of the team leader. Circumstances dictated otherwise and once again, such a responsibility fell on my shoulders.

Fortunately, the team members were supportive and forgiving enough to forgive me for minor outbursts or my lack of experience in solving some of the problems related to task coordination. The use of Sprints via GitHub was Phil’s initiative and I think it was a successful choice. We could have used better certain collaborative work tools (Slack maybe?), but all that was something I also intended to learn through experience and from others along the project. Beyond Phil, I have to admit that none of the others in the group could bring much wisdom to the use of them.

It’s not the first time I mention how frustrating it was for me to synchronize Unity builds between the different development branches or how difficult it is for me to be faithful to Scrum techniques. I’m not one to question them of course, but I just don’t find them to flow satisfactorily in a totally virtual environment like ours. Admitting my shortcomings in these areas may cost me some points against me, but that is precisely what this work of reflection is about. At the same time, I believe that my strong points are that I know to a greater or lesser extent all the stages of development, which enables me to provide solutions or work on them directly, helping to unblock possible pitfalls as you can surely appreciate through the reading of these texts.

Although practice has shown me on several occasions that I am able to complete a project on time and -relatively- in good shape, alone or with a group of collaborators, the reality demands me to continue deepening in this type of techniques so as not to jeopardize the project of starting my own independent development studio.

List of figures

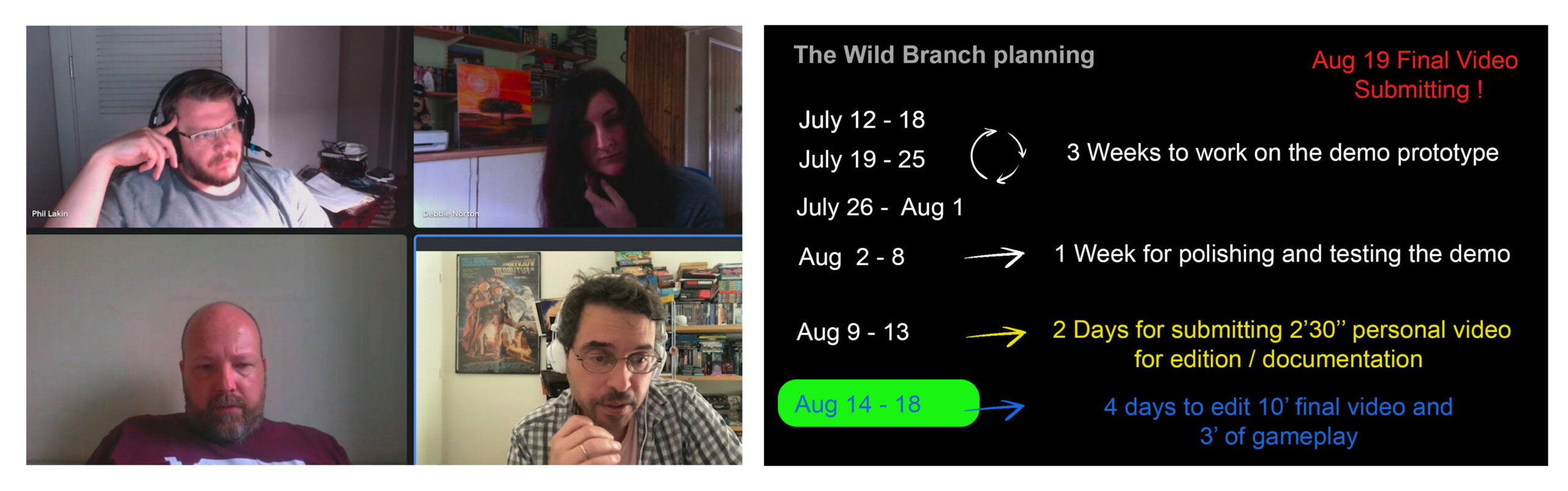

Fig 1. Wild Branch weekly talk and general planning towards the assignment completion. Screen capture by the author.

Fig 2. Article from The Telegraph newspaper published in 2014. (c) The Telegraph Group UK

Fig 3. Humorous death sequence for Keep It Burning. Capture by the author.

References

Hatzoupoulos, S. 2017. ‘Advances in Clinical Audiology’. Published byIntech. National and University Library of Zagreb. Croatia.

Le Roux, Mariette. 2014. ‘Cavemen’s ‘rock’ music makes a comeback’. [online]. Available at: <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/10702186/Cavemens-rock-music-makes-a-comeback.html> Published by The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group. [Accessed 2 July 2021].

Spoonhower, J. 2021. ‘Indie Reflections: Making Anew Part 13‘. ‘Wireframe magazine issue 41. Raspberry Pi Publishing.

Gagh, E. 2018. ‘Telltale Employees Left Stunned By Company Closured. No Severance‘. [online]. Available at: <https://kotaku.com/telltale-employees-left-stunned-by-company-closure-no-1829272139> [Accessed 12 August 2021]. Published by www.kotaku.com

Rivera, J. 2014 ‘Inside The Video Game Industry’s Culture Of Crunch Time‘. [online]. Available at: <https://kotaku.com/telltale-employees-left-stunned-by-company-closure-no-1829272139> [Accessed 12 August 2021]. Published by www.fastcompany.com

Hall, C. 2020. ‘Cyberpunk 2077 has involved months of crunch, despite past promises’. [online]. Available at:<https://www.polygon.com/2020/12/4/21575914/cyberpunk-2077-release-crunch-labor-delays-cd-projekt-red>. [Accessed 13 August 2021] Published by www.polygon.com

Williams, M. 2013. ‘Game Devs: When Does Crunch Cross The Line?‘ [online] Available at: <https://www.gamesindustry.biz/articles/2013-10-23-game-devs-when-does-crunch-cross-the-line> [Accessed 12 August 2021]. Published by www.gameindustry.biz

Gibbous A Cthulhu Adventure. Youtube. 2017. ‘Stuck in the Attic – Making An Indie Game Documentary‘. [online] Available at: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vm709GBFCIo&t=2753s> [Accessed 14 August 2021].